The ride continues

Early Riders, again

I struggled with the story of early horse domestication in Raiders. The research, going for about a decade, resembled a volley between Alcaraz and Sinner. My head spun following the back and forth between proponents and opponents of Botai in Kazakhstan as the site of the first domesticated horses. Moreover the arguments for earlier domestication made plausible the idea that the steppe people whom archeologists refer to as Yamnaya (from a site in Russia), invaded Europe with horses in the 4th millennium BCE. I never liked this story, which underlines a lot of ideologically heavy views of European history (e.g., Gimbutas). In recent years scholars working with aDNA (ancient DNA) have significantly clarified the chronology of horse domestication. Based on this work, I am trying to pull trying to pull together a simple narrative, even though we can no longer speak about domestication, but domestications.

I struggled with the story of early horse domestication in Raiders. The research, going for about a decade, resembled a volley between Alcaraz and Sinner. My head spun following the back and forth between proponents and opponents of Botai in Kazakhstan as the site of the first domesticated horses. Moreover the arguments for earlier domestication made plausible the idea that the steppe people whom archeologists refer to as Yamnaya (from a site in Russia), invaded Europe with horses in the 4th millennium BCE. I never liked this story, which underlines a lot of ideologically heavy views of European history (e.g., Gimbutas). In recent years scholars working with aDNA (ancient DNA) have significantly clarified the chronology of horse domestication. Based on this work, I am trying to pull trying to pull together a simple narrative, even though we can no longer speak about domestication, but domestications.

As the ice age receded and steppe turned to forest (12,000 years ago), the population of horses declined. The relationship between horses and humans began to change, as humans began to “harvest” nearby herds for meat (similarly to the way Plains Indians managed the buffalo herds). Horses chose to live in proximity to human settlements, where campfires drove off biting insects and scared away feline predators. Around 5,500 years ago humans began to milk horses, in the same manner as they had milked cattle, goats and sheep, millennia earlier.

From the moment humans began to managing horse herds, the necessity of riding them arose, simply because horses move faster than cattle and humans. We simply can’t imagine a herder following the herd on foot. So people began to ride. Probably children or youngsters, changing their mounts from time to time, because these horses were not strong enough to support a rider for any period of time. As I mentioned in Raiders, the fact that these horses had lived close to human settlements for some time, that the mares had been milked by humans, and the foals raised with humans, enabled the first intrepid riders to stay on top of these somewhat less unpredictable animals (but what modern horse is predictable?)

At this time, five or six races of horses grazed between between Spain in the west and the Altai in the east. What I call them races represented clusters of somewhat homogenous DNA, neighboring races overlapping. The horses in Iberia were quite different from the ones in Poland, the ones in Poland from the ones in the steppe, not so much.

Extensive traces of one of these races has surfaced in Botai. There we have significant evidence of domestication: short generation gaps (because domesticated horses breed earlier than wild ones), skeletal and dental deformities due to being bitted and ridden, mares milk proteins in the excavated ceramics. However, the latest aDNA studies suggest that the Botai horses are not the ancestors of the modern horse, but of the wild Przewalski horse. This surprising conclusion suggests that 1) the Botai breeding experiment was ultimately unsuccessful, and 2) someone else came up with a better alternative.

Indeed 4,000 years ago, a millennium after the Botai horse, breeders in Pontic-Caspian steppe developed a race of horses with two genetic modification for better riding. One supported stronger spines and the other lowered the animal’s stress. This meant these horses could be ridden further, longer, and with more predictable behavior. Scholars refer to this new breed as the second domestication, or Dom2 for short.

The superior riding features of the Dom2 were so apparent, that within a short period of time it superseded all other races of horses for domestic use. Within 200 years we find hardly any other races being managed. The other races either remained wild, became feral like the Botai, or died out. Perhaps the Tarpans, a race that went extinct in the 19th century, descended from these, with or without an admixture of Dom2.

The success of the Dom2 in a short period of time suggests that people knew what a good horse looked like. They already rode their local races of horses for herding purposes, so adopting the Dom2 was an easy decision for them. We can imagine the first horse traders fanning out across Europe and bringing the new, improved horses to eager buyers further west.

The Dom2 enabled real riding and chariot driving. The arrival of the Dom2 coincided with the warrior culture of the Bronze age. Suddenly you have the ritualized violence of the Iliad and the Mahabharata with the clash of charioteers, spears and arrows. The first such battle attested in Europe is at Tollense in northern Germany, probably involved 4,000 combatants as well as horses, about 3,300 years ago.

So note here, it was not the Yamnaya peoples from the steppe who brought warfare to Europe. They brought us milk, cheese and ensured that many Europeans would be lactose tolerant, if they have sufficient Yamnaya DNA. They probably did have horses, but these would have been the ones more dangerous to their riders than to their neighbors.

Is there then a connection between the Dom2 and warfare? The pre-Bronze age, pre-Dom2 horse herders of Europe did not leave behind them signs of organized violence. That makes sense because their horses were not strong enough to pull chariots or steely enough to engage in battle. So Dom2 horses indirectly enabled the kind of carnage Homer describes in the Iliad (about 3,100 years ago): “ As through deep glens rageth fierce fire on some parched mountain-side, and the deep forest burneth, and the wind driving it whirleth every way the flame, so raged he every way with his spear, as it had been a god, pressing hard on the men he slew; and the black earth ran with blood…. thus beneath great-hearted Achilles his whole-hooved horses trampled corpses and shields together; and with blood all the axletree below was sprinkled and the rims that ran around the car, for blood-drops from the horses' hooves splashed them, and blood-drops from the tires of the wheels.”

The Orlov Trotter

For centuries Russia and Ukraine were famous for their vast herds of small, hardy horses, raised in the steppe by either Tatars or Cossacks. As European fashions traveled east, riders sought bigger, more elegant horses, with smoother paces. Stud farms replaced open grazing, and aristocratic breeders adopted what they considered to be more scientific methods. Glory, patriotism and sporting prizes motivated these enthusiasts. Often money was no object. Count Orlov, a favorite of Catherine the Great, spent 60,000 rubles – a multi-million dollar equivalent in modern terms – to purchase an Arabian stallion, Smetanka, so called for his cream-colored coat. Before dying from overexertion or homesickness, Smetanka sired four colts and one filly with a harem of big-boned German horses, and the Orlov Trotter was off to the races.

For centuries Russia and Ukraine were famous for their vast herds of small, hardy horses, raised in the steppe by either Tatars or Cossacks. As European fashions traveled east, riders sought bigger, more elegant horses, with smoother paces. Stud farms replaced open grazing, and aristocratic breeders adopted what they considered to be more scientific methods. Glory, patriotism and sporting prizes motivated these enthusiasts. Often money was no object. Count Orlov, a favorite of Catherine the Great, spent 60,000 rubles – a multi-million dollar equivalent in modern terms – to purchase an Arabian stallion, Smetanka, so called for his cream-colored coat. Before dying from overexertion or homesickness, Smetanka sired four colts and one filly with a harem of big-boned German horses, and the Orlov Trotter was off to the races.

They played an exceptional role in cavalry as well as husbandry, in drawing elegant carriages and even on the race tracks. Grand Duke Dmitry Konstantinovich, a cousin of the last emperor, owned one of the most successful Ukrainian stud farms and raised a number of race track idols, including Byvaly and Kvaleny. The Grand Duke transferred his private land to the Provisional Government in 1918, but this did not save the domain from the chaos and disorganization that the October Revolution ushered in.

The new Soviet breeders association eventually took the Orlov Trotters in hand and protected the breed. It turned out that animal breeding was a matter taken seriously by Soviet science, though one wonders how much of the success of the program came from keeping on a few of the old Grand Duke’s stable hands, versus listening to university-trained specialists. Orlov Trotters set record speeds not only in the Soviet Union, but also in races abroad, in Berlin and Helsinki.

The collapse of the Soviet Union again threatened the existence of the breed, as many breeding horses were sent to the slaughterhouse for want of buyers. Franco-Russian cooperation partly saved them, as the French began to run “Russian days” at the Vincennes Race Track to showcase the breed. Today there are 800 brood mares in Russia, and 300 brood mares in Ukraine. Since 1,000 brood mares is considered a minimum to maintain a healthy blood line, we have another reason to hope that the terrible war there will come to an end. The legacy of the cream-colored Arabian stallion lives on, for now.

The Great Game and the Struggle for Horse Power

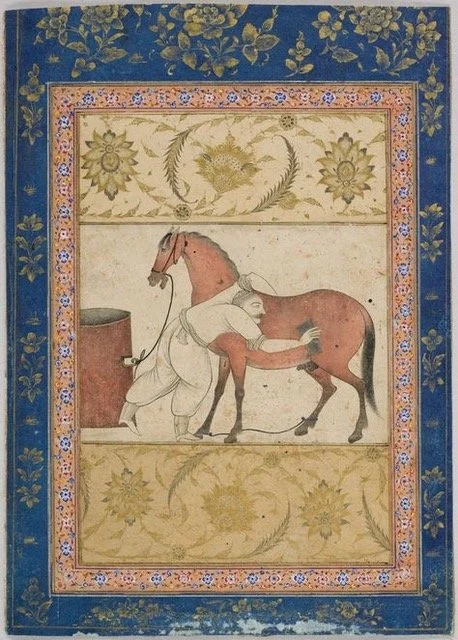

Horse and Groom, courtesy Harvard Museums

Over 3,500 kilometres separate Calcutta from Bukhara, 3,900 from there to Saint Petersburg: colossal distances in the late 19th century. Although empires, like nature, abhorred vacuums, clear-thinking statesmen in the respective imperial capitals thought these empty territories could be left alone. Their agents on the ground, however, in Orel or in Lahore, took a great deal of interest in “empty” Central Asia, provoking a rivalry that came to be known as the Great Game. While any single, simple explanation for this complex story can mislead us, the little-discussed role of horse power in the Great Game provides us with new insights.

Far from being empty and peripheral to history, Central Asia has been a major breeding ground for horses for over 2,000 years, since the days of the Scythians. These ancient nomads sent the fabled heavenly horses to the emperor of Han China. Central Asian horses powered the empire of Tamerlane. The Mughals recruited Central Asian horsemen for their conquest of India, in addition to importing over 100,000 horses a year as remounts. Afghanistan’s founding monarch, Ahmad Shah Durrani, came from a family of horse traders. Much of the wealth of Central Asia derived from the horse trade, which made up a significant percent of the value of all goods traded along the Silk Road.

This trade did not, as some history manuals tell, drop off in modern times. In the 19th century the nomads of Central Asia, Kazakh, Kirghiz, Turkmen and Uzbeks, made a fine living from their trade with both Russia and China, as reported in the contemporary reports of English travellers, like Thomas and Lucy Atkinson.

Indeed, the Great Game started with a Briton trying to break into this lucrative business. Haunted by the memory of Ahmad Shah Durrani’s multiple, destructive invasions in the mid-18th century and the subsequent Rohilla troubles (the latter were Afghan horsemen native to India), Britain’s East India Company invested heavily in horse breeding at Pusa, in today’s Bihar. After years of effort, cavalry experts complained that native horses remained unsatisfactory. In 1819, William Moorecroft, a Scottish veterinarian and the frustrated manager of the EIC stud, convinced himself and a few influential authorities in Calcutta that India’s defence depended –not on breeding undersized horses locally but– on procuring superb Turkmen horses from the emir of Bukhara. His quixotic mission there ended in failure, for the Russians and the Chinese were already paying such good money for horses, that the emir saw no reason to offend them by doing business with the Briton. Turkmen horses remained an object of desire for Alexander “Bukhara” Burnes, who likewise failed to make any diplomatic or commercial breakthroughs on his mission there in 1832. Unable to trade with Bukhara, both Moorcroft and Burnes considered Afghan horses to be a good second best for the EIC cavalry, an opinion that encouraged British involvement in that country and contributed to the catastrophic 1st Anglo-Afghan war in 1841.

Proponents of a forward policy in Afghanistan and the lands beyond were undeterred by that setback, especially as Russia’s conquest of Bukhara in 1868 brought Cossack cavalry ever closer to the Punjab. British enthusiasts of Central Asian horse power eyed the Teke Turkmen, still independent from Russia and breeders of one of Asia’s most famous races, the Akhal Teke. These animals, still rare today, exhibit astonishing adaptations to the Karakum desert, including the spectacular, metallic sheen of their coats. Some amateurs of the Akhal Teke imagine they are the descendants of the heavenly horses of Chinese lore. British agents visited Turkmen chiefs in 1873 to explore the possibility of including them in treaty relationships, similar to those extended to the Baluch or to the Gulf Arabs. The Russians, rankled by the British expedition to Kabul in 1879, pre-empted this with a lightening campaign against the Teke, annexing the last independent horse breeders of Central Asia in 1885. If the Great Game had been about horses, then the Russians won it.

The defence of India received succour from an unexpected equine resource: Australian Whalers, a hardy cross between English thoroughbreds and Hackneys. For the first time the Indian Empire found a secure and economical supply of remounts for its cavalry, especially as shipping rates fell through the rest of the century. In 1903 the Indian Army fielded 29 regiments of horse, while the princely states (under indirect British control) provided another 20. The maharajas of Gwalior, Baroda, Patiala and Indore showed off these units during the Imperial Durbar of that year. The superb turn out of their horses gainsaid old Moorcroft’s complaint about the inferiority of local breeds. They disproved Moorcroft once again with their outstanding performances in the celebratory racing and polo matches against British regiments mounted on Whalers. The justification to import Whalers boiled down to the fact that the British troopers were beefier than Indian sowars, and so needed bigger horses.

Because of the vagaries of European power politics, India’s cavalry arm never confronted the Cossacks, but the Great Game concluded with a coda that evoked the spirits of Moorcroft and Burnes, and at the same time sounded the last post for India’s cavalry. The latest successor to Ahmad Shah Durrani, Afghanistan’s King Amanullah ascended to the throne in 1919, and sought to make his mark by invading what he thought would be a war-weary and sedition-wracked British India. With modest battlefield success he could have reasonably expected to return to Kabul’s rule the Afghan tribes on the British side of the contested Durand line. A major Afghan victory might even lead to the collapse of British rule in India, as the king’s Bolshevik advisors hinted to him. In any case Amanullah would be able to add “ghazi” to his titles.

The Third Anglo-Afghan war, as it became known, had some traditional features that would not have surprised veterans of the first or second of these conflicts. Regiments like Skinners Horse, raised in the 18th century to fight the Rohillas, scraped with the familiar foe in engagements that the official history would later characterise as the last clashes involving lances and cold steel. British victory, however, was sealed not by horse power, but by air power. Already in 1918 Col. T.E. Lawrence had experimented with the use of airplanes against the Ottoman Turks in Palestine. The success of that campaign had convinced the Indian Office to deploy the RAF to the Northwest Frontier. The planes flying sorties over the Afghan lines were ancient BE2 biplanes, whose service dated back to the Imperial Durbar of 1903. Despite their obsolescence, their bombing raids discouraged the Afghans from concentrating for attack, preventing them from making much progress past the Durand line. Further bombing of Jalalabad, the Afghan winter capital, humiliated Amanullah, and convinced him to request peace negotiations. At the conclusion of hostilities, Amanullah decided, spitefully, to ban the export of horses to India, as if horses had been a significant element in his defeat. So ended the 3,000-year-old horse trade between India and Central Asia. The age of horse power had ended, along with the Great Game. Was it out of whimsy or a sense of irony that Amanullah offered King George V, during his state visit to London in 1928, a Persian illustrated manuscript on hippology? This book is now in Windsor castle. That colourful album is a reminder just how long the importance horse power lasted, and how much of world history can be explained through this lens. Even the history of the Great Game, with its twists and turns, gains new clarity when we consider the role horses played in it.

This piece first appeared in Caravansarai, the magazine of the Royal Society for Asian Affairs, used with their kind permission.

Coffee with Jean-Louis Gouraud

Jean-Luis Gouraud, author of numerous works on horses and horsemanship, is one of Europe’s most respected equine experts. He travelled on horseback between Paris and Moscow. We had a coffee together on September 9th.

We haven't seen each other since the summer of 2024. Our mutual friend, Bruno de Cessole, was nominated for several literary prizes this fall, including the Renaudot. I noticed that his novel, "Tous finit bien que finit", mocks literary prizes in particular, and that this could offend the jurors (whom the book treats as dupes). J-L replies that the president of the Renaudot committee is astute enough to appreciate Bruno's provocation.

J-L apologizes for not having been able to convince his publisher, Actes du Sud, to acquire my book for a French edition. They balk at undertaking the translation, which might prevent them from making any money on the book. J-L shows me a summary that Jean Pierre Digard has made of Raiders. I briefed J-L on the ongoing translations into Russian, Chinese, and Turkish, noting that the Chinese translation will be an adaptation, to conform to the party line, or at least, Chinese sensibilities. We note that Emperor Qian Long is in good odor with the party, as he is the one who bequeathed China its current borders, notably Xinjiang.

Returning to Raiders, the only flaw J-L mentioned is the poor quality of the illustrations. He is currently preparing a new book where he needs to deal with the difficulties of reproductions, especially since he wants images in color. His book deals with the “conversion of the horse” to Christianity, and how saints acquired mounts they certainly never rode, like St. Paul on the road to Damascus or St. Martin sharing his robe with a beggar. J-L believes that painters preferred equestrian figures, since they looked more heroic than pedestrians.

Speaking of illustrations, J-L recounts how, while working on his book about Giuseppe Castiglione, a Jesuit painter at the court of Qiang Long, he visited the Palace Museum in Taipei. The curators took him to the third or fourth seismic-resistant basement to show Castiglione's original scrolls. Among other things, he had the chance to see the life-size "100 Horses" scroll, each animal depicted in a unique position. J-L was able to reproduce this image in the resulting book with a large, fold-out insert.

We talk about the gifts given to the emperor by the steppe peoples, the importance of which several paintings by Castiglione demonstrate. I used one of these images in Raiders. This tradition of gift-giving continues today. First the Soviet Union and now Turkmenistan have been offering Akhal Teke horses to heads of state in the purest tradition. J-L Gouraud had already told me about the misfortunes of the Akhal Teke presented to Mitterrand, which the president entrusted, without the knowledge of the public, to his clandestine daughter Mazarin. According to J-L, the president's error of judgment consisted not in privatizing an official gift, which he was entitled to do, but using the state apparatus to bring it from Moscow for his benefit. We discussed another story, that of the young English diplomat charged with taking charge of an Akhal Teke presented to Queen Elizabeth II. Finally, I told J-L the story of the American ambassador to Ashgabat who did the dirty work of refusing an Akhal Teke horse, because US government lacks both imagination and tact. At the same time, Xi Jinping, like Qian Long, receives these horses as gifts every year.

J-L laments the fact that, on the one hand, the Turkmen frequently offer mediocre or even defective Akhal Teke horses. One of the problems with this breed is that the Turkmen claim to manage their studbook, whereas in the Soviet Union, this was Moscow's role. The majority of the breed does not live in Turkmenistan, but in Kazakhstan or elsewhere. The Turkmen are suspected of introducing English thoroughbred blood to create horses better suited to racing.

This operation is understandable, in the sense that the Akhal Teke horse has lost its raison d'être. The Turkmen developed a horse with endurance and undemanding in terms of hydration. They used it to raid caravans and kidnap slaves from their neighbors. As a Russian officer of the time said, "Once we eliminated raiding, this horse no longer had a reason to exist."

All domesticated animals, J-L continued, are human creations. The large Shire and the small Shetland are the result of generations of breeding with specific uses in mind. Now, J-L laments, breed diversity is threatened by the reduced use of horses in the modern world. "They only have two functions today: racing and sport." The Germans breed good horses for dressage and competition, while the English breed racehorses.

While breeders continue their work patiently—knowing that the creation of a breed can take two or three human generations—science can now perfect a tailor-made animal through selection a gene that determines speed, for example. While a complex organism like a horse has several million genes, we have identified certain specific genes that have a direct impact on desirable traits. The English company Genus PLC is developing animals that give birth without veterinary intervention, or that are more resistant to heat waves. Now, using the CRISPR process, we can insert the selected gene into a cloned embryo—as Argentines are now doing to polo poneys. It's only a short step, warns J-L, to create super-powerful men. The temptations will be strong.

We also discussed Ludovic Orlando's book, which is being published in English this month and is the subject of my review in "Asianreviewofbooks.com." J-L congratulates the author for clarifying several points about the history of horses, notably the Przewalski lineage. I salute the astute diplomat who dismisses the Saudis and the Native Americans without offending them.

J-L is going to Russia to dedicate a horse cemetery, containing the remains of the horse ridden by Alexander Pavlovich for his triumphant entry into Paris in 1814. During the 19th century, more than a hundred celebrated horses found their final resting place there. Abandoned by the Bolsheviks, damaged by the Nazis, the Soviets forgot its very existence. J-L managed to convince the Russians that this site merited restoration. After 30 years of struggle, a rededication will take place in April 2026.

Tumultuous Trade and the Heavenly Horses

The USA’s current embrace of opportunistic trade deals underscores the reality that international trade has since been, for 2,000 years, a messy affair where competition, conflict and outright warfare coexist…..

The USA’s current embrace of opportunistic trade deals underscores the reality that international trade has since been, for 2,000 years, a messy affair where competition, conflict and outright warfare coexist. Prior to World War II and the GATT agreement of 1947, trade often followed the flag, with countries using gunboatsand strong-arm tactics to gain outlets for their products. Trade provided not just wealth, but a measure of national security—with real war being a common outcome of trade wars. No story better illustrates this continuum between war and trade than the origins of the Silk Road. China’s Han dynasty (202 BCE – 220 AD) faced a powerful trade challenge in the form of the nomadic Hun empire. After almost one hundred years of conflict, the Han succeeded in upending what they perceived as an unfair trade relationship, but at an enormous cost. What are the lessons for statesmen and mercantilists today?

In theory, trade is a mutually beneficial relationship where two parties exchange what each side has in surplus, for what each side lacks. In the case of Han China and the Hun empire, the Chinese needed horses. The core regions of the Han empire provided poor conditions for raising these animals, so essential for transportation and warfare. China’s wet, warm climate did not suit horses. Land-hungry farming occupied much of what might have been used for pasture. Even the soil lacked trace minerals like selenium, essential for horses growth and health.

To the north, the steppes of what is now Mongolia thronged with horses, who thrived in the cooler temperatures and abundant grasses. The horse-breeding peoples of the steppes sold thousands of horses to their Chinese neighbors, from the beginning of steppe horse breeding, around 1500 BCE. In return they received manufactured goods, silks, and foodstuffs.

The steppe people had to sell their excess horses, because in good years the herds grew too big for the available pastures. But when they rode down to China in their massive trading caravans, the prices they received for their horses would fall, reflecting oversupply. Often, protesting against these lower prices, the steppe people raided China, kidnapping and plundering. Paradoxically, not only did these raids enrich the steppe people, they forced the Chinese to buy more horses and so drove the price of horses back up. Inasmuch as the Chinese resented the greedy and violent behavior of their neighbors, they wound up rewarding the raiders. Worse was to come.

As long as the steppe peoples were divided into smaller tribes, China could defend itself against these pin-prick raids. By 209 BC, however, an ambitious steppe chief named Modun took control of his tribe, and using extreme violence, federated the peoples of the northern steppe into a great empire, the Huns. Modun centralized trade, war and diplomacy into a tool for extracting the maximum wealth from China. Faced with a monopolistic partner, the Chinese had to pay high prices for horses, or incur a major attack. The Huns kept Han China in a constant state of war or submission for a century.

Finally, a new emperor, the Han Wudi, or “the Martial Emperor” decided to break the Hun horse monopoly. But how? The Huns controlled pastures in a wide arc around northern China. To the west lay the Taklamakan desert. To the south, the mountains of Yunan. It seemed unlikely that China could find another, competing supplier.

Wudi consulted the oracles of the I Jing, divining that heavenly horses would be found in the far west. The emperor’s spies traveled 2,000 miles, to today’s Uzbekistan, encountered the Ferghana horses, superior to anything the Huns could supply.

The Han Wudi sent trading missions to Ferghana. Some were captured on the way and enslaved by the Huns. Others reached their goal , but Ferghana’s rulers refused to sell horses to China out of fear of Hun reprisal. When Ferghana executed on a particularly obstreperous envoy, the emperor took this as an insult to China, and vowed revenge.

In 104 BCE he assembled an army of 100,000 soldiers, with over 100,000 pack animals. The expedition crossed the Taklamakan desert and scaled the Tian Shan range with passes at 12,000 feet. They laid siege to Ferghana and forced the surrender of 30 heavenly horses and several hundred ordinary horses. It had taken a year from the expedition to reach Ferghana, and one year to return to China. When the emperor saw the fine horses, he exclaimed, “The heavenly horses are come from the West. I shall ride them into the Mountains of Heaven.”

The expedition cost the Han several years of tax revenues. The heavenly horses did not flourish in China, and worse, their offspring grew up spindly and weak. Some Chinese men of the pen condemned the expedition as a “folie de grandeur”. It looked like China would be condemned to trade with the Huns, who would continue to raid China whenever they liked. But the expedition for the heavenly horses set a bigger trend into motion.

The horse breeders of the west learned that China would pay top dollar for their herds, and that it was possible to bring these horses from as far away as Ferghana. This broke the Hun monopoly. This horse caravan trail, from West to East is what we now call the Silk Road.

The story of the heavenly horses represent an early instance of a major state going to war for both trade and national security, and not the last time either. When China looks at its trading partners for metal ores, petroleum or microchips, do not imagine for a second that the history of the Han Wudi emperor is far from their minds. As the post-World War II trading order weakens, we may see the pattern of raiding and trading reemerge.

Weather and Steppe Invasions

“Our geldings are fat”, the Mongol warriors pointedly told Genghis Khan. They were asking their chief, indirectly, when they would ride to war. The Mongols typically launched their campaigns in late summer, when their horses had had their fill of grasses, could survive long marches, and gallop quickly in and out of combat. The more grass grew on the steppe, the more geldings the Mongols could ride to war. A succession of good springs and summers would swell the herd with horses.

“Our geldings are fat”, the Mongol warriors pointedly told Genghis Khan. They were asking their chief, indirectly, when they would ride to war. The Mongols typically launched their campaigns in late summer, when their horses had had their fill of grasses, could survive long marches, and gallop quickly in and out of combat. The more grass grew on the steppe, the more geldings the Mongols could ride to war. A succession of good springs and summers would swell the herd with horses.

So, I was puzzled to read in “Climate Change and War Frequency in Eastern China over the Last Millennium” by David D. Zhang, Jane Zhang, Harry F. Lee and Yuan-qing He in Human Ecology (Aug., 2007), that the authors identified a correlation between bad weather and the outbreak of warfare, the opposite of what I would have expected.

Today we are concerned about global warming, but our ancestors feared cold spells. Zhang et al. write, “Temperature is probably the most important climatic variable influencing human societies, which are particularly vulnerable to long-term temperature changes. Temperature fluctuations directly impact agriculture and horticulture, exacerbate natural disasters, and can adversely affect plant, animal, and human rates of disease.” A relatively small drop in average temperatures can have a huge impact on crop yields, and even greater on animal survival rates. During a zuid, or frost, herders can lose 90% of their herd, even if the average drop is just 2%.

They then turn to wars, using tabulations recorded by the Editorial Committee of China’s Military History. This organ recorded 899 wars between the fall of the Tang and end of Manchus, almost one war per year. The intensity of these conflicts in terms of duration and deaths yields a plot of peaks and valleys showing the deadliest decades. Not surprisingly, the highest peaks of violence accompany the fall of the Song, the Yuan, and the Ming. Scholars often attribute these dynastic collapses to poor crops, famine and ensuing peasant revolts. In this respect, climate and warfare seem to correlate well. A lot of wars in China consisted of revolts, often initiated by desperate and starving farmers.

However, when the authors analyze southern and northern China separately, the data shows something else. In southern China war is highly correlated with cold weather, with 2.4 times more wars than in warm weather. In the north the correlation is only 1.6. Still, cold weather in the north of China might have weakened the resistance of the sedentary populations, without devastating the pastoralists herds, making it easier for the steppe warriors to invade. The fall of the Ming dynasty in 1644 is typical in this regard. This decade was one of the coldest on record. Peasant revolts wracked the dynasty. The pastoralist Manchus waited for their chance—the last Ming emperor committed suicide.

Zhang et al. argue that the Manchus were able to organized themselves into the formidable banner regiments, devise their own alphabet, raise their ruling chiefs to imperial rank, and invade China because they faced the same terrible climatic conditions as the Chinese. I find this argument unconvincing. It could well be that Ming China’s collapse harmed their own economic well-being. They had grown wealthy from selling horses to their Chinese neighbors, benefiting from the Ming’s reluctance to buy from their old enemies, the Mongols. Perhaps the loss of this horse trade encouraged Nur Haci to act. But if he had lost many of his horses to a zuid, he would hardly be in a position to defeat a Ming army of 100,000 cavalry. There is no direct evidence that the Manchu herds had shrunken in size. So, it is very likely that the cold weather did not affect the horses, and Nur Haci’s geldings were fat and ready to attack when word of the emperor’s suicide came.

Studies of average temperature probably do not capture micro-climatic events like zuids, while they are better at explaining bigger agricultural crises. The Little Ice Age in Europe, for example, contributed to the 30 Years War (1618-1648). I do not find climate per se a convincing explanation for Genghis Khan or Nur Haci, although such findings are frequent in the literature. We need more research on good growing years on the steppe, to see if these correlate with the success of the Mongols and Manchus, as anecdotal clues suggest.

The Land of Good Horses

The first thing we learn about Iran, is that it is a land of good horses. In his monumental cuneiform inscription at Naqsh-e Rostam, King Darius I (550-486) writes, “This country, Persia, which Ahuramazda gave to me is a good country, full of good horses.”

Summary of a lecture given to the Iran Society and the Royal Society for Asian Affairs

January 22, 2025

It is great to see here tonight so many familiar faces, but it’s humbling to realize that many of you are real experts in horses and in Iran. That makes you a great audience to consider the question I want to explore tonight: Iran being a land of good horses, has that been a good thing or a bad thing historically?

Before we go into this, let me say something about how I came to write my new book, Raiders, Rulers, and Traders. Initially I had been struck with the cultural similarities between China, India and Iran, the three great civilizations of ancient times, and I came to realize that some of this similarity originated from the huge role horses played in the histories of these countries. As I delved further into the matter, however, I learned that Iran’s relationship to the horse was very different from those of India and China. We’ll see some of those differences surface in the course of this talk.

The first thing we learn about Iran, is that it is a land of good horses. In his monumental cuneiform inscription at Naqsh-e Rostam, King Darius I (550-486) writes, “This country, Persia, which Ahuramazda gave to me is a good country, full of good horses [iyam dahyâuš Pârsa tyâm manâ Auramazdâ frâbara hyâ naibâ uvaspâ, https://www.livius.org/sources/content/achaemenid-royal-inscriptions/dnb/.

The Darius inscription at Naqsh-e Rostam: “A land of good horses”

The king’s boast is corroborated by the Greeks: Herodotus describes the Nissean horses and their hoofbeats like thunderclaps. Xenophon, who led th Athenian cavalry, praises the equestrian prowess of Cyrus the younger (408-401). He must have had equine envy since Cyrus’ cavalry numbered in the tens of thousands, while Athens had only 600 troopers.

The Greeks speak of many breeds. These breeds fascinated Iranians from centuries ago. Here is a manuscript of a hippology manual, a fârsnameh, from the Khalili collection. As far back as the time of the King of Kings, different breeds were bred, like the Nissaean, and different colours reflected distinct lineages. The ancient Persians knew the adage, “Horses for courses,” reflecting the vast and varied ecosystems of the country. Modern Iran is 7 times bigger than the UK with many types of desertic, mountainous, and semi-tropical. These environments all provided plenty of pastures.

The Khalili Collection Farsnâmeh

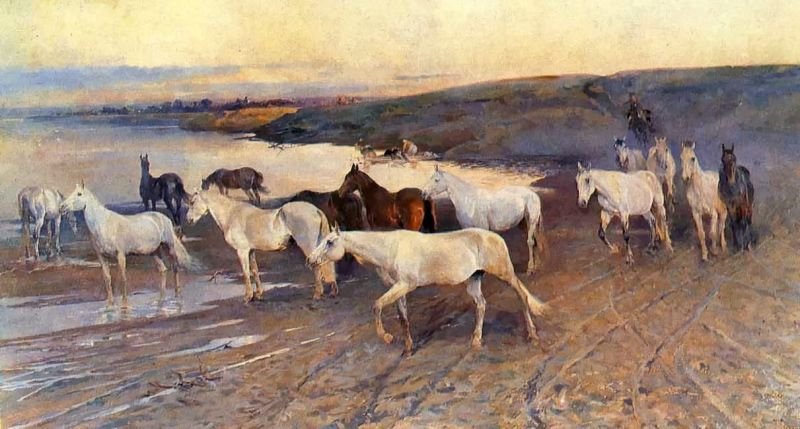

What do we notice in this painting, from a XVth century Bukharan artist? It’s spring in the steppe, the dasht, where succulent flowers make the world look like one big Persian carpet. It shows the excellent conditions for horses in Iran, outdoor grazing, no need for fodder, no stabling. Horses raised outdoors don’t develop psychological problems. They grow up more resilient, stronger, and more aggressive in war. Iran enjoys conditions like this in Azerbaijan, Media (Kurdistan) or Shiraz/Fars. This is from Sadi’s Bustan manuscript in the Fogg Museum, Cambridge, MA, “Darius III and his herder”.

Sa’di’s Bustan MS Fogg Museum, by a Bukharan artist, Darius visits his horse herds

Let’s take a deeper look at the climate of Iran, and especially in comparison to neighboring countries.

Here is a map of Eurasia’s climates:

The green zones are too hot with too much rain. Rain softens horses hooves and makes them unsuitable for long marches. There are too many weird plants growing which could give horses fatal colic. Rain leaches minerals out of the grass, so that horses cannot grow to be strong and fast. Moreover in the green zones, favorable for agriculture, there is too much competition from farmers for land. Indeed it is India and China where we find these green zones. No less an authority than Babur complains of Hindustan, which he just conquered, “there are no good horses.”

The red zones are too dry for large scale horse raising. These are the lands of the camel, raised by Bedouin in the Arabian peninsula and by the Baluch (an Iranic people) in southeast Iran, southern Afghanistan, southern Pakistan, going into the Thar desert of India.

The salmon and goldish colored-zones offer goldilocks conditions for horses, not too hot, not too cold, not too dry, not too wet. Here grows the luxuriant grass we saw in the previous illustration. These zones, too, are good for irrigation-based agriculture only, which as we will see is an important feature of Iran.

As we see in this map the Eurasian steppe abounds in such grasses, and therefore in horses. In ancient times, half of the world’s horses lived on the steppe. This was the native habitat of the horse and the cradle of horsebreeding peoples.

These peoples traditionally raided the four great settled empires, Iran, Rome, India and China. The reason for that is not that they were more violent or greedy than their settled neighbors. Since the horse population grows faster than the human one, horse breeders blessed with several years of good weather find themselves with too many horses. Pasture can become scarce. So there is a natural tendency for horse breeders to expand when they can into neighboring lands. This is what Iran’ steppe neighbors did.

Iran needed all the horse power it could muster to defend itself from invasions from these northern neighbors, despite its own good horses. These invasions have been a constant element of Iranian history, starting with the Scythians and the Huns, and ending with the Uzbegs and the Turkmen

The conflict between steppe horse breeders and the Iranians is the origin of many of the stories of the Shâhnâmeh, the Iranian national epic. Now this epic opposes the horse breeders, the “Turanians” against the agriculturalist Iranians. The Iranians have a rich tradition of dry farming based on elaborate irrigation. But the dichotomy between Turan and Iran in the epic is not very clear. The paladins of both sides fight on horseback using similar gear, they play polo together, they lasso horses. The two armies seem very similarly matched. It’s very different from the Indian or Chinese narratives about steppe invaders, who are depicted as much more alien.

One distinction the Shâhnâmeh makes is based on Zoroastrian symbolism, the black horse and white horse. This goes back to the Avesta – the ancient holy book of the Zoroastrians. The white horse symbolises Iran, the land of the pure, the truth. The black horse represents the lie. Here’s a illustration of how persistent that image is, a 19th century painting of the Qajar Shah Fath-ali defeating the enemies of Iran, in this case the Russians. How often is Fathali depicted on a white horse. So if, always, Ali abu Talib, the focus of Shiite devotion.

To keep out the steppe invaders, the Iranians did not just rely on horse power. They also build defensive walls, similar to the Roman walls in northern England and on the Rhine, and like the Great Wall of China.

These two photos are suggestive of the fate of China versus the fate of Iran. The Chinese, under various dynasties maintained the wall as a separation beween the steppe and the core lands of China all the way down to the 19th century.

The Great Wall of Gorgan, Gorgan Province, Iran

The Great Wall of China

In Iran it was different. The Arabs conquered the steppe, and defended a frontier much further north, on the Amu Darya River. Over time they forgot why there had even beem a wall. They thought perhaps Alexander the Great built it to keep out Gog and Magog, the legendary forces of destruction. Increasingly they allowed Turkish horse breeders to settle inside the Caliphate as military slaves, Mamlukes. So did later Iranian rulers like the Samanids, and the Ghazavids (themselves descended from steppe Turks. Then a big change occurred.

In 1035 a Turkmen chief of the Seljuk clan, Arslan Israil, petitioned Mas’ud of Ghaznah, the Sultan of Khorasan (eastern iran) as follows:

“We number 4,000 families. If my lord were to issue a royal patent and allow us to cross the Gorgan river and settle in Khorasan, he would be relieved of worrying about us, for there would be plenty of space for us in his realm, since we are steppe people and have extensive herds of sheep. Moreover, we would provide additional manpower for his army.” This request should have set off alarm bells. But instead Mas’ud made a very bad political mistake, endorsing the first major breakthrough of purely steppe people into central Iran. They spread through his realms causing chaos

”That region became ruined, like the dishelved tressses of the fair ones, or the tearful eyes of the loved ones, as it became devastated by the pasturing of the Turkmen’s flocks,” as one contemporary historian put it.

Why was this such a big deal? Consider difference between farmers and herders. Farmers are tied to the land, dependent on irrigation and requiring protection from the central government. The horse breeding pastoralists are very different. They enjoy Mobility, and this gives them Political agency and autonomy. They can afford to ignore their chiefs, their khans. If they are unhappy they can elect a new khan and ride away as they fancy.

After the initial period of chaos, the Seljuks tried to be good rulers in the Iranian monarchical tradition, but their clansmen were unruly. Here is a Qajar painting from the Brooklyn Museum, showing Sultan Sanjar trying to protect a peasant crone from the depredations of his own entourage. In the story, told by Saadi, the sultan is a model of justice. In historical fact, his own clansmen overthrew Sanjar and he died in captivity, and Iran descended again into chaos. The Turkmen, horse breeders, despite this history of bad governance, rule Iran down to 1923. If this were not bad enough, along came more horse breeders (1219)

“As far as our horses’ hooves will carry us”, summarizes the Mongol ambition of conquest. They did not set out to conquer the world. They only wanted to conquer the world’s pastures. This made Iran, the land of good horses, an obvious target. Many Iranians remember the Mongols as the most destructive invaders fo Iran. There are several points to keep in mind:

· Much of the disorganisation of Iran had already begun under the Seljuks

· Second, the Mongols indeed entered Iran on a scale X times the Seljuks: 1 milluon vs 20,000, with 20 million heads of livestock

· Third the Mongols did try to reconstruct Iran, but it was a different Iran, because of much greater number of horse breeders. 1 out of every 3 Iranians was a nomad, converting farmland to pasture. As the European traveller William de Rubruck reported, “There used to be sizeable towns lying in the plains, but they were for the most part destroyed by the [Mongols] since the area affords very good grazing lands.

· This is the beginning of the ”steppe type” nomadism in the Zagros.

· Because Iran is such a land of good horses, the Mongols were never expelled from Iran, unlike from China (1368)

Yet Mongol and later Timurid Iran remained a wealthy and poweful country, and a great civilizational one at that. Some consider the late Mongol era as the Golden Age of Iran (the title of Fry’s 1976 work).

How could this be? Consider:

Horses themselves represented a huge source of wealth for Iran. In my book I talk about how the silk road might more accurately be called the horse road, since livestock were the biggest commodity by volume to travel across it. Unlike silk or other luxuries, this merchandize transported itself, and cost nothing as it pastures along the way.

An example of this business in Iran is provided by the Mongol Nikudari tribe. They had settled in Sistan and Herat. Where they developed a thriving business selling horses to both China and India. Their wealth gave them the status of a state within a

state. For years none of Iran’s rulers had any control over them. Then Tamerlane decided to tame them. He defeated them in battle, and then confiscated 100,000 horses from them, breaking their power forever. The remnants of the Nikudari fled into the fastness of the Hindukush mountains, where their descendants, the Mongol-looking Hazara people, live today.

Both the Mongol Yuan dynasty and their successors the Ming dynasties sought to acquire Iranian horses, which is suggestive of how famous these were at the far side of the Eurasia continent.

In fact, the grandchildren of Tamerlane sent delegation with gift horses to the Yong Le Emperor of the Ming, as a way of opening up further trade in horses with China. He received the Iranians in a pompous ceremony in the newly built Forbidden City. After inspecting the horses brought from Samarkand and Herat, he complained about their quality, and asked them next time to bring horses from Azerbaijan instead. This stung because Azerbaijan was the one part of Iran that the Timurids did not control.

I find it amazing that the emperor of China knew enough about Iranian horses to have a preference for one breed over another.

Trade in horses took place by sea as well as land. There was a high demand for horses in southern India, whose sultans and maharajas were constantly at war with those of northern India. Since the northerners controlled the flow of horses from Afghanistan and Central Asia, the southerners had to buy horses from the Persian gulf. Already in the 14th century, this was a flourishing trade, in the hands of Persian merchants.

But in the beginning of the 16th century the Portuguese muscled their way into the Indian Ocean and took over this trade. They were not content to just replace local traders. They brough technological innovations. They designed and built special boats with stalls to keep the horses protected from the rolling of the waves, and portals allowing grooms to sweep clean the horses’ manure into the sea. The improved safety and hygiene of the transportation ensured that the Portuguese cargo survived the sea journey much better The Portuguese suffered a fraction of the losses of the local traders. As a result they made fabulous returns. The vice-roy of India wrote to the king of Portugal, “His majesty should know that everyone who wishes to rule in India has need of horses. The trade returns three times, four times, five times the money invested. It is crazy (literally, locura).” When you visit Goa today and see the golden tomb of St. Francis Xavier, know that the gold was earned by the horse trade.

Now we come to the era which represents perhaps the apogee of Iranian horses. John Chardin, the Anglo-French travelers, visited the court of Shah Abbas in 1666. He wrote: “The horses of Persia are the most beautiful in the East. They are taller than the English saddle horses.” Equally, he praised Iranian equestrian prowess: “They race, placing twenty tokens on the ground one after the other, and pick them up again in the same way on the return> without slowing down the race. Some riders stand straight on their feet on the saddle, and thus make the horse run at full speed.” He describes polo and throwing the javelin. He adds, “The exercise of the bow on horseback is done by shooting backwards ata cup, placed on the end of a mast six score feet high. Even kings practice it. Shah Abbas excels in this.”

To give a full picture of the importance of horses for Shah Abbas, one must read Chardin’s description of the royal stables. These stables preceeded the hall of audience, such that ambassadors had to walk through them to reach the king. “Beside the great entrance of the Royal Palace, were twelve of the most beautiful horses in the King's stable, fixed on each side, covered with the most superb and magnificent harnesses that one could see in the world. Four harnesses were of Emeralds, two of Rubies, two of colored Stones mixed with Diamonds, two others were of enameled Gold, and two others of fine smooth Gold. Besides the harness, which was of this richness, the saddle, that is to say the front and the back, the pommel and the stirrups, were covered with precious stones affixed to the harness. These horses had large hanging tufts very low, some in raised embroidery of gold and pearls, others of very fine and very thick gold brocade, surrounded by tufts and gold cheekpieces with pearls. The horses were attached to the feet and the head with large trefoils of liver and gold, to nails of fine gold.”

One of the horses, permanently saddled and waiting, was designated for the Hidden Imam, or the Savior to come at the end of time, so that he could immediately ride out and overcome the forces of injustice. But in the end, it was not the Mahdi who came to save Iran.

Iran’s 18th century was one of turmoil. Let us remember that in the population of 6 million, as much as 25% were horse breeding pastoralists, descended from the Turks and Mongols, and also from the Kurds who had become even more pastoralist under the Mongols. This had political consequences.

When the Afghans of Qandahar revolted against the shah, and made their way towards the capital, Esfahan, the beys and khans of the pastoralist tribes took their sweet time to organise any resistance. The rebels captured and plundered Esfahan, murdering most of the royal family. Iran fell apart. It took titanic efforts on the part of Nader Khan, later Nader Shah, to mobilize the Turkmens into an army and eject the invaders from the country. These efforts cost the hollowed out state so much that Nader was hated, and later assasinated. The country returned to a tribal free for all. The wealth of Iran had been based on trade, especially trade in horses—which did not require a central government. This is what makes me think that horses were too much of a good thing for Iran.

The emergence of the Iranian tribes as we know them, also saw the emergence today's modern horse breeds. There are many stories about how this or breed is the oldest, but this is unlikely. Breeds can’t be older than the tribe, and most tribes go back to the18th century as currently constituted. As an example, the famous Akhal Teke breed was developed by the Teke Turkmen. In the 18th century the Teke tribe chose to become independent of the Shah, and so migrated into a remote area in today’s Turkmenistan. They made their living by slave raiding: swooping across the Gorgan River and kidnapping Iranians for sale in Central Asia slave markets. To accomplish this, they bred a horse that could travel across the desert for three or four days without drinking water, and to gallop off with a victim tied to its croup. Such a highly-trained, calorie-hungry horse cost much effort to breed and raise—so it only made sense if compensated by the lucrative business of slaving. Once the Russians conquered the Teke Turkmen in 1888, they repressed slaving. They were eager to take advantage of the wonderful Akhal Teke horses, and were surprised to see them decline in numbers and quality. That horse occupied a specific social and political role in the Teke tribe, and once that role ceased, the extinction threated.

Examples of some famous Iranian breeds include;

Top to bottom, Dareshuri (Qashqai), Ail Arabian, Bakhtiyari, Turcoman, Kurdish

At the end ot the 18th century one of many Turkmen clans, the Qajars, that had fought for Nader overcame rivals to reestablish the state, but in the meanwhile things have changed. The Qajars experienced a severe loss of territory and especially horse rich pastures in Azerbaijan, north of the Gurgan, and the Oasis of Herat. I wonder if this alone did not create a changed balance of power against the horse breeders and in favor of the central government. In any case the a modern state arose that was antipathetic to these horsemen.

In the 20th century the government decided to supress pastoralism and settle down the horse breeders. Throwing the baby out with the bathwater, this was an economic catastrophe, reducing the contribution of pastoralism to from some 30% of GDP at the beginning of the century to 3% by the 1970s. For the first time in its history. Iran had to import meat. Since horses were expensive to raise and unnecessary in the absence of pastoralism, the famous breeds of Iran, like the Akhal Teke earlier, began to dissappear. But the surpression of horse breeders solved the political problem they posed.

In this context, two individuals stand for their efforts to preserve Iran’s equine heritage. Both were women, with American connections. Maryam Gharagozlu, born to an American mother, became responsible for liason between the government and the tribes, a thankless role in the political context of the time. She took on the cause of Iran’s Asil Arabians, trying to convince the World Arab Horse Association to recognise Iranian stock. Louise Firuz, American born, rediscovered a rare breed of poneys in the forest of the Caspian coast, and tirelessly tried to promote and protect the Turkmen horse. Both women paid for their advocacy with jail sentences, but now Iran grudgingly recognizes the importance of its equine patrimony. Growing numbers of horse enthusiasts in Iran, many of them women, are maintaining Iran as the land of good horses.

Maryam Gharagozlu

Louise Firouz

Horses for the Emperor of China

The immense crowd of warriors, mandarins, eunuchs and servants pack the courtyards and terraces of the newly built Forbidden City, straining to get a view of the emperor. His dais rises so high above the ceremonial bridge he seems to be floating in the sky with the apsaras. He is pronouncing criminal sentences on a common prisoners, heads drooping down by the weight of wooden cangues locked around their necks. Some he orders flogged, some maimed, very unlucky ones decapitated. A handful are pardoned. Sentences are carried out on the spot by impassive, muscled executioners. Gore quickly pools on the granite paving stones of the courtyard of justice. Normally honored guests, ambassadors from far away Samarkand, are being forced to watch the proceedings, with an increasing sense of foreboding.

The immense crowd of warriors, mandarins, eunuchs and servants pack the courtyards and terraces of the newly built Forbidden City, straining to get a view of the emperor. His dais rises so high above the ceremonial bridge he seems to be floating in the sky with the apsaras. He is pronouncing criminal sentences on a common prisoners, heads drooping down by the weight of wooden cangues locked around their necks. Some he orders flogged, some maimed, very unlucky ones decapitated. A handful are pardoned. Sentences are carried out on the spot by impassive, muscled executioners. Gore quickly pools on the granite paving stones of the courtyard of justice. Normally honored guests, ambassadors from far away Samarkand, are being forced to watch the proceedings, with an increasing sense of foreboding.

This is not a scene out of Turandot, but neither is it a typical day of justice for the denizens of the Forbidden City. The Yongle emperor of the Ming, whose name we usually associate with refined blue and white porcelain, has orchestrated this show of power and cruelty to send a message to the embassy. Some years earlier Samarkand’s ruler, Timur, or Tamerlane, had thrown Yongle’s ambassadors into prison, and assembled a huge army to invade China. Timur dreamt of reestablishing the empire of Genghis Khan from Baghdad to Beijing. His advanced age, a freak blizzard and too much alcohol all contributed to Timur’s death on the frontier of China, and the resulting retreat of his army. The recently enthroned Yongle narrowly escaped a dangerous encounter with an undefeated world conqueror. The ceremony today in the Forbidden City is part of his plan for revenge.

Why did the ambassadors throw themselves into the mouth of beast? It had taken them over a year to reach Beijing from Samarkand (then the capital of Timur’s heirs, an empire that included today’s Uzbekistan, Afghanistan and much of Iran). They could have simply let Yongle stew. But their empire in the 15th century was a major exporter of fine horses, and Ming China one of the biggest customer. The horse trade explains why the ambassadors undertook this arduous, and potentially dangerous mission to Beijing.

When the ambassadors first crossed into Chinese territory, riding at the head of a caravan of precious, they met with generous hospitality. The local governors put them up in comfortable guest houses, fed their horses with fresh alfalfa, organized friendship banquets, and entertained their guests with singing and dancing girls and boys, who also extended post-show companionship. The Iranians had anticipated more frosty treatment, before they could offer their apologies and present their horses to the emperor, so they were very pleased with all these attentions. They let down their guard as they approach Beijing. Here they promptly underwent a cold bath.

These proud horsemen, who never walked anywhere, were ordered to dismount at the outside-most gate of the Forbidden City. They had to walk for what seemed like an eternity between serried ranks of soldiers, armed to the teeth with bows, maces, swords and halberds. At each gate they expected to come into the imperial presence, but found always yet another walkway flanked by soldiers in blackened steel armor, and another 100 yards to trudge forward. They had to trudge up stairs to what looked like an audience hall, and then exit the out the back to yet another hall. Then Yongle kept them waiting, standing, in the sun, for hours while he conducted his exercise of justice. Deeply humiliated, the ambassadors from Timur’s realms kept them composure and waited for his summons.

At last the emperor dismissed his executioners, and summoned the ambassadors to come forward. The armed guards pushed them forward so that they almost involuntarily performed the kow-tow, or fell flat on their faces. They offered their diplomas, written in vermillion ink, explaining their mission in the several mutually understood languages- Persian, Turkish and Chinese. At the signal from the presiding mandarins, the gift horses from the ambassadors’ caravan now ambled into the courtyard for the emperor’s inspection. It was customary, in trade with China, to offer part of the merchandise as a gift, in order to dispose the buyer kindly for the commercial goods.

Horses from the western realms, then ruled by Timur’s heirs, were famous throughout Asia. China had been procuring them for centuries. 1,400 years before, the Han dynasty of China had launched an army 100,000 strong across the steppe in order to bring back just 30 horses from Ferghana, not far from Samarkand. More recently, Yongle had sent the great admiral Zheng Ho to transport horses back from the Persian Gulf, an immense undertaking. Horses so transported to China were famed as “1000 mile runners” and “Celestial Horses”.

In the Chinese heartland wet climate and waterlogged soils provided poor conditions for raising horses. This is why China always had to import them. Where pastures existed, land-hungry farmers gradually pushed out herders. Nearby Mongolia and Tibet raised poneys used to hard work and harsh weather. These served as the workhorses for the Chinese empire, but not the mounts of an emperor. Horses from Samarkand grew two or three hands taller than any of these animals. Now as the grooms presented the gift horses and showed off their points, the ambassadors peered anxiously up as the dais to ascertain the reaction of the emperor.

His response was not long in coming. “I understand that Azerbaijan has fine horses, belonging to Yusuf, Sultan of the Black Sheep Turkmen.” His words hit the ambassadors like a whip across the face. One part of Iran that they had not managed to control was the rich grazing land of Azerbaijan, ruled by their wily rival, Yusuf. Not only was Yongle apparently dissatisfied with the gift horses, he compared them unfavorably to those of their enemy. The emperor summarily dismissed them and retired to his inner chambers. Worse was in store for the embassy.

The fact that the emperor of China knew about the horses of Azerbaijan and the distant sultan Yusuf testifies to the fundamental importance of horses in Chinese statecraft. “Horses are the pillar of the state. When horses lack, the state will fall,” opined a Han dynasty general. China used its diplomacy to control the steppe, to ensure a steady supply of horses for cavalry, post horses and civilian use. It sought fine horses for prestige, and even for geomancy, i.e., magic, as the different coat colors of horses symbolized for them the cardinal directions, white for the west, black for the north, grey for the east, and sorrel for the south. Horses played an important role in religious ceremonies. The imperial family was interred with sacrificial horses. This why all embassies from the horse-rich west brought racy steed to the imperial court.

There was little evidence that the latest gift horses were having the effect desired. As the ambassadors sat glumly around in their guest quarters, they heard a great tumult. Stepping outside, they learned that the emperor had gone riding on one of the gift horses and had been thrown, breaking his arm. They immediately set out for the emperor’s bridle path, and threw themselves flat in the dust, with their arms stretch out in front of them, awaiting their sentences—to be executed like the criminals of the morning’s ceremony.

The emperor had indeed angrily ordered his courtiers to go round up the ambassadors and to execute them summarily. But as they set his arm and put it in a sling, his wrath dissipated. By the time he remounted another horse, he had regained his composure. He rode imperiously up to the Iranians, lying prostrate beside the road, and ordered them to stand up. “The horse you gave me”, he explained calmly despite his pain, “was no good. It threw me. When nations wish to establish friendly relations, it is good that their gifts be worthy.”

The frightened ambassadors replied, with much servility, that this particular horse had belonged to the great Timur himself, and that therefore it was the worthiest present they could have made to the emperor. “I understand”, said Yongle, “But then perhaps it has not been ridden in a long time and therefore is no longer good for the saddle”. The emperor rode off, leaving the Iranians to meditate on this close call, and on the sorry success of their embassy so far.

In the end the emperor must have concluded that he had taught the Iranians enough of a lesson. They had seen his might, his anger, but also his mastery of statecraft. They were allowed to return to Samarkand and tell of the Great Ming Khan (as they styled him in Persian), and there would be no more threats of invasion ever again. Yongle left them with a parting barb, “When you come back remember to bring me horses from Azerbaijan!” Perhaps the ambassadors managed to do this, because they did launch subsequent missions, and secured the right to trade with China, and most importantly, to sell their horses. So in this respect, at great expense and risk to their lives, the ambassadors sent from Samarkand accomplished what they had set out to do.

Timur’s empire broke up, but the new rulers of Samarkand continued to sell horses to China down to the middle of the 19th century. Much of the prosperity of Central Asia and western China depended on this trade. It was only in the 20th century, when petroleum-powered transportation replaced horses for military purposes, that the former realms of Timur turned into a poverty stricken backwater. When I bought a horse in Herat in 1975 the dealer promised me “you can ride this horse to China”. I took this to be a nice verbal flourish, but perhaps somehow the memories remained of the once flourishing horse caravans that traveled to distant Beijing.

Deconstructing Nomad Empires

In the Bible Adam and Eve get to name everything. That was the last recorded instance of people agreeing what names should be given to what. Confucius argued that misnaming things would lead to societal chaos. History writing requires naming the protagonists, and defining their relationships. Not coincidentally modern history writing emerged more or less at the same time as the science of numismatics, since ancient coins proved to be a sure method for identifying the names of ancient rulers and their dynastic connections to one another.

In the Bible Adam and Eve get to name everything. That was the last recorded instance of people agreeing what names should be given to what. Confucius argued that misnaming things would lead to societal chaos. History writing requires naming the protagonists, and defining their relationships. Not coincidentally modern history writing emerged more or less at the same time as the science of numismatics, since ancient coins proved to be a sure method for identifying the names of ancient rulers and their dynastic connections to one another.

How do we know when we name an ancient people if this name corresponded to their own sense of whom they were? Identity politics existed in ancient times just as today. Peoples often assumed prestigious names for political reasons. The European Avars, according to their steppe rivals, did not descend from the formidable Avars of Asia—they had been slaves to the latter, and they had run away and misrepresented themselves as the real thing. The so-called Heavenly Turks subdued a number of steppe peoples, the Uyghurs, the Nine Oghuz, the Karluks, and the Kirghiz. But because their life-style as horse breeders appeared so similar to the Muslims of Oxiana, all of them wound up being recorded in Persian and Arabic texts as Turks, and this name has stuck.

Modern identity and even international politics place great importance on ethnicity, often seeking to identify the roots of current ethnic groups in a more or less legendary past. Reality offers us intersectionality, an inconvenient dilemma for historians and nationalists alike. I stayed once in a “Kurdish” village in southeastern Turkey. The male villagers, surprisingly however, spoke Turkish while the women spoke Arabic. When my hostess found out that I understood Arabic, she was tickled pink. Whenever I spoke to her husband in Turkish she remonstrated with me, “Ihki ‘arabi, ya Dawud!”

In this book I try to avoid essentialism around either ethnicities such as Turks, Pashtuns, Tajiks or Tibetans, i.e., the assumption that the people we know today existed in the same guise in the past. For example, some historians emphasize the continuity of ancient peoples, using erudite, but often controversial, onomastics to connect the ancient Tokharians with the later Wusun or the Yuezhi. Are these the “same people” or are they merely the same name for different peoples, like the Welch of Britain and the Welsche of Switzerland? In any case the reader still must follow, as in a Russian novel, a huge cast of hard-to-remember names.

To make the narrative easier to follow, and avoid having to split hairs about the language or the DNA haploid types of ancient peoples, I do not name specific protagonists unless absolutely required to do so. I found it unavoidable to speak of the Scythians (but do not differentiate between them and the Sokolatai, Sauromates, Sakas and Alans), Turks (in all the flavours in which they came in ancient times), the Khitans (but not the Xianbei, the Ruanran or the Avars). I also pass over the many exonyms, i.e., the names that the Indians or the Chinese used to refer to groups like the Turks or the Afghans. To help readers who may want to consult a standard history like the Cambridge Histories, I append a list of all my simplifications. I also call all the rulers of the steppe “khan” at the expense of the qaghans, tekins, tarkhans and idikuts. I can’t help but thinking that Edward Lear had a hand in inventing these titles.

Likewise I avoid the essentialism “nomad”. The word suggests to most readers an immutable and isolated lifestyle that sets the nomads apart from the farmers. Recent fieldwork emphasizes the continuities between herding and farming, and between rural and urban living in the steppe. What does appear to be a major distinction between the two lifestyles is horse breeding. This gets around the problem that some peoples practice long distance migration (like the Mongols) involving the whole community, whilst others practice transhumance (like the Kurds of Iran), where only the shepherds move the flocks. But both the Mongols and the Kurds raise horses. This is a full-time occupation, and gives the peoples who practice it a distinctive lifestyle, even if their agricultural and animal husbandry practices may differ from one region to another. Some of them herd camels, some buffalos or even yaks, but the constant feature of the horse breeders is that they live symbiotically with large herds of horses. Horse breeding as a lifestyle is not only highly characteristic of the steppe peoples, it is also a very homogeneous and conservative lifestyle. Archaeological and anthropological evidence points to a strong continuity in the lifestyle of the steppe horse breeders, even as we see the Turks replacing the Scythians, and the Mongols replacing the Turks.

I don’t use the word “tribe”, if I can help it. Many readers assume “tribe” has a fixed meaning, whilst it does not. Anthropologist delight in deconstructing the use of the word tribe by steppe peoples. One investigator asked the Shahsevan Turkmen of Iran about their tribal organisation. Informants mentioned the existence of 4 to 18 tribes and issued conflicting genealogies. Few of the tribal names seemed older than the early 1800s. The steppe tribes can best be thought of as political parties. Just as the Democrats of Thomas Jefferson’s time are not today’s Democrats of Biden, the Tatars of Genghis Khan’s time are not the Tatars of the Russian Federation. Like political parties, tribal groups have emerged and disappeared. In lieu of “tribe” I prefer to use the word peoples. For very large groupings a term like confederation is justified. When we talk about a small group with a defined marital policy (i.e., endogamous vs exogamous), we can call it a clan. Tribe is anything in the middle and maybe nothing.

I have had to make the distinction between settled and steppe states, but the distinction should be less than meets the eye. French anthropologist J.P. Digard contrasts the steppe society of “horsemen” (cavaliers) and the settled society of “squires” (écuyers). Both groups used horsepower for political purposes. The steppe is more coloured by the horsemen because they form such a big percent of the population. In the steppe everyone rides. In settled society horse riding is a sign of social class. The squires play an important role in the settled states because they represent the horse power.

Both kinds of states ruled settled and steppe peoples, though in different proportions. States originating on the steppe relied on horse power to govern. Their khans did not build monumental capitals or palaces, but rather travelled around their realm with magnificent tent encampments. They did this to show themselves to the ever-mobile horse breeders on whose political support they relied for power. Their power was based on loyalty, not on ownership of land. Rulers of settled states often based their power on ownership of lands (crown lands). They built capital cities that functioned symbolically like mandalas, focusing the power of the heavens onto a single city, to a specific palace, to a throne room. Settled people came to pay obeisance to the king. The king did not travel to see his subjects.

Settled and steppe states practiced violence in an equal measure. As the Pirate of Penzance sung, “But many a king on a first-class throne/If he wants to call his crown his own/ Must manage somehow to get through/More dirty work than ever I do.” Both settled states and steppe states jealously managed the balance of power between themselves and other actors. Clients who waxed too powerful underwent preemptive attacks. Struggling independent states found themselves victims of their neighbour’s ambition. Frequently raiding served to test the balance of power. The outbreak of wars, less frequent, not all of them very violent, allowed states to adjust the balance of power by small degrees, rather than risking existential conflicts. In the same way the kings and the khans managed the rivalries between princes, sub-chiefs, and ministers, banishing and executing them occasionally, to preserve their own prestige. When they flinched in this duty the vizier or sub-chief did not hesitate to make replace his master. Kings and khans also promoted, demoted and executed the members of their harem, and again for the same reason, to recalibrate the power dynamics the women’s quarter. Likewise the women replaced the kings and khans with their brothers or sons when the opening arose. I see little difference in the behaviour of the settled states or the steppe ones in this respect. Uneasy lies the head that wears the crown.