The Great Game and the Struggle for Horse Power

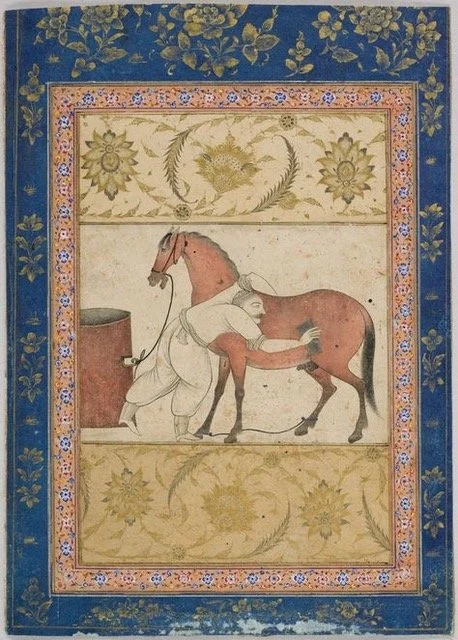

Horse and Groom, courtesy Harvard Museums

Over 3,500 kilometres separate Calcutta from Bukhara, 3,900 from there to Saint Petersburg: colossal distances in the late 19th century. Although empires, like nature, abhorred vacuums, clear-thinking statesmen in the respective imperial capitals thought these empty territories could be left alone. Their agents on the ground, however, in Orel or in Lahore, took a great deal of interest in “empty” Central Asia, provoking a rivalry that came to be known as the Great Game. While any single, simple explanation for this complex story can mislead us, the little-discussed role of horse power in the Great Game provides us with new insights.

Far from being empty and peripheral to history, Central Asia has been a major breeding ground for horses for over 2,000 years, since the days of the Scythians. These ancient nomads sent the fabled heavenly horses to the emperor of Han China. Central Asian horses powered the empire of Tamerlane. The Mughals recruited Central Asian horsemen for their conquest of India, in addition to importing over 100,000 horses a year as remounts. Afghanistan’s founding monarch, Ahmad Shah Durrani, came from a family of horse traders. Much of the wealth of Central Asia derived from the horse trade, which made up a significant percent of the value of all goods traded along the Silk Road.

This trade did not, as some history manuals tell, drop off in modern times. In the 19th century the nomads of Central Asia, Kazakh, Kirghiz, Turkmen and Uzbeks, made a fine living from their trade with both Russia and China, as reported in the contemporary reports of English travellers, like Thomas and Lucy Atkinson.

Indeed, the Great Game started with a Briton trying to break into this lucrative business. Haunted by the memory of Ahmad Shah Durrani’s multiple, destructive invasions in the mid-18th century and the subsequent Rohilla troubles (the latter were Afghan horsemen native to India), Britain’s East India Company invested heavily in horse breeding at Pusa, in today’s Bihar. After years of effort, cavalry experts complained that native horses remained unsatisfactory. In 1819, William Moorecroft, a Scottish veterinarian and the frustrated manager of the EIC stud, convinced himself and a few influential authorities in Calcutta that India’s defence depended –not on breeding undersized horses locally but– on procuring superb Turkmen horses from the emir of Bukhara. His quixotic mission there ended in failure, for the Russians and the Chinese were already paying such good money for horses, that the emir saw no reason to offend them by doing business with the Briton. Turkmen horses remained an object of desire for Alexander “Bukhara” Burnes, who likewise failed to make any diplomatic or commercial breakthroughs on his mission there in 1832. Unable to trade with Bukhara, both Moorcroft and Burnes considered Afghan horses to be a good second best for the EIC cavalry, an opinion that encouraged British involvement in that country and contributed to the catastrophic 1st Anglo-Afghan war in 1841.

Proponents of a forward policy in Afghanistan and the lands beyond were undeterred by that setback, especially as Russia’s conquest of Bukhara in 1868 brought Cossack cavalry ever closer to the Punjab. British enthusiasts of Central Asian horse power eyed the Teke Turkmen, still independent from Russia and breeders of one of Asia’s most famous races, the Akhal Teke. These animals, still rare today, exhibit astonishing adaptations to the Karakum desert, including the spectacular, metallic sheen of their coats. Some amateurs of the Akhal Teke imagine they are the descendants of the heavenly horses of Chinese lore. British agents visited Turkmen chiefs in 1873 to explore the possibility of including them in treaty relationships, similar to those extended to the Baluch or to the Gulf Arabs. The Russians, rankled by the British expedition to Kabul in 1879, pre-empted this with a lightening campaign against the Teke, annexing the last independent horse breeders of Central Asia in 1885. If the Great Game had been about horses, then the Russians won it.

The defence of India received succour from an unexpected equine resource: Australian Whalers, a hardy cross between English thoroughbreds and Hackneys. For the first time the Indian Empire found a secure and economical supply of remounts for its cavalry, especially as shipping rates fell through the rest of the century. In 1903 the Indian Army fielded 29 regiments of horse, while the princely states (under indirect British control) provided another 20. The maharajas of Gwalior, Baroda, Patiala and Indore showed off these units during the Imperial Durbar of that year. The superb turn out of their horses gainsaid old Moorcroft’s complaint about the inferiority of local breeds. They disproved Moorcroft once again with their outstanding performances in the celebratory racing and polo matches against British regiments mounted on Whalers. The justification to import Whalers boiled down to the fact that the British troopers were beefier than Indian sowars, and so needed bigger horses.

Because of the vagaries of European power politics, India’s cavalry arm never confronted the Cossacks, but the Great Game concluded with a coda that evoked the spirits of Moorcroft and Burnes, and at the same time sounded the last post for India’s cavalry. The latest successor to Ahmad Shah Durrani, Afghanistan’s King Amanullah ascended to the throne in 1919, and sought to make his mark by invading what he thought would be a war-weary and sedition-wracked British India. With modest battlefield success he could have reasonably expected to return to Kabul’s rule the Afghan tribes on the British side of the contested Durand line. A major Afghan victory might even lead to the collapse of British rule in India, as the king’s Bolshevik advisors hinted to him. In any case Amanullah would be able to add “ghazi” to his titles.

The Third Anglo-Afghan war, as it became known, had some traditional features that would not have surprised veterans of the first or second of these conflicts. Regiments like Skinners Horse, raised in the 18th century to fight the Rohillas, scraped with the familiar foe in engagements that the official history would later characterise as the last clashes involving lances and cold steel. British victory, however, was sealed not by horse power, but by air power. Already in 1918 Col. T.E. Lawrence had experimented with the use of airplanes against the Ottoman Turks in Palestine. The success of that campaign had convinced the Indian Office to deploy the RAF to the Northwest Frontier. The planes flying sorties over the Afghan lines were ancient BE2 biplanes, whose service dated back to the Imperial Durbar of 1903. Despite their obsolescence, their bombing raids discouraged the Afghans from concentrating for attack, preventing them from making much progress past the Durand line. Further bombing of Jalalabad, the Afghan winter capital, humiliated Amanullah, and convinced him to request peace negotiations. At the conclusion of hostilities, Amanullah decided, spitefully, to ban the export of horses to India, as if horses had been a significant element in his defeat. So ended the 3,000-year-old horse trade between India and Central Asia. The age of horse power had ended, along with the Great Game. Was it out of whimsy or a sense of irony that Amanullah offered King George V, during his state visit to London in 1928, a Persian illustrated manuscript on hippology? This book is now in Windsor castle. That colourful album is a reminder just how long the importance horse power lasted, and how much of world history can be explained through this lens. Even the history of the Great Game, with its twists and turns, gains new clarity when we consider the role horses played in it.

This piece first appeared in Caravansarai, the magazine of the Royal Society for Asian Affairs, used with their kind permission.